Now Reading: The History and Evolvement of Asian Animation

-

01

The History and Evolvement of Asian Animation

The History and Evolvement of Asian Animation

Asian animation has carved a distinct place in the global entertainment landscape, influencing generations of viewers and shaping the international perception of animated storytelling. Known for its unique artistic styles, culturally rich narratives, and innovative production techniques, Asian animation encompasses a broad spectrum of media, from Japanese anime to Chinese donghua and Korean manhwa adaptations.

Understanding the history and evolution of Asian animation provides insight into how these works have captured global audiences while reflecting the cultures and philosophies of their countries of origin.

The Early Days of Asian Animation

The roots of Asian animation can be traced back to the early 20th century, when animators began experimenting with hand-drawn motion and narrative storytelling. In Japan, pioneers such as Junichi Kouchi and Seitaro Kitayama began producing short films in the 1910s, often inspired by Western animation techniques while incorporating local folklore and traditional art.

These early works were simple in technique, often silent, and used limited frame rates due to technological constraints. Despite these limitations, they laid the foundation for a uniquely Japanese style of storytelling, emphasizing moral lessons, mythological themes, and expressive character design. Meanwhile, in China, early animated shorts combined traditional ink painting techniques with rudimentary animation, reflecting the country’s rich artistic heritage. Korean animation also began developing during this era, though it was heavily influenced by imported Japanese works due to historical and cultural exchanges.

Post-War Expansion and the Rise of Anime

The post-World War II era marked a significant turning point for Asian animation, particularly in Japan. The devastation of war created a demand for affordable entertainment, and animation studios began to flourish.

The 1960s saw the rise of Osamu Tezuka, often called the “God of Manga,” whose work on Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atom, 1963) popularized serialized animated television in Japan. Tezuka’s innovative use of limited animation techniques, expressive character designs, and dynamic storytelling set the template for modern anime.

During this period, Asian animation began to solidify its identity, characterized by stylized visuals, exaggerated expressions, and an emphasis on narrative depth.

Themes explored ranged from futuristic sci-fi to historical drama, appealing to audiences across age groups. TV shows, feature films, and adaptations of popular manga started gaining traction, establishing Japan as a global hub for animated entertainment.

Technological Advancements and Artistic Innovation

The 1980s and 1990s were transformative decades for Asian animation, fueled by technological innovation and international exposure. The rise of color television and advances in cel animation allowed for more visually sophisticated productions.

Anime films by directors like Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata at Studio Ghibli elevated Asian animation to cinematic artistry. Films such as My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and Grave of the Fireflies (1988) demonstrated the emotional depth and technical mastery achievable through hand-drawn animation.

At the same time, South Korea and China expanded their animation industries. South Korean studios began outsourcing work for international productions, gaining expertise in 2D and, later, digital animation. Chinese animation, or donghua, experimented with traditional ink painting techniques and early digital animation, gradually creating a unique voice distinct from Japanese anime. These developments allowed Asian animation to diversify in style, technique, and thematic focus.

The Digital Revolution and Modern Asian Animation

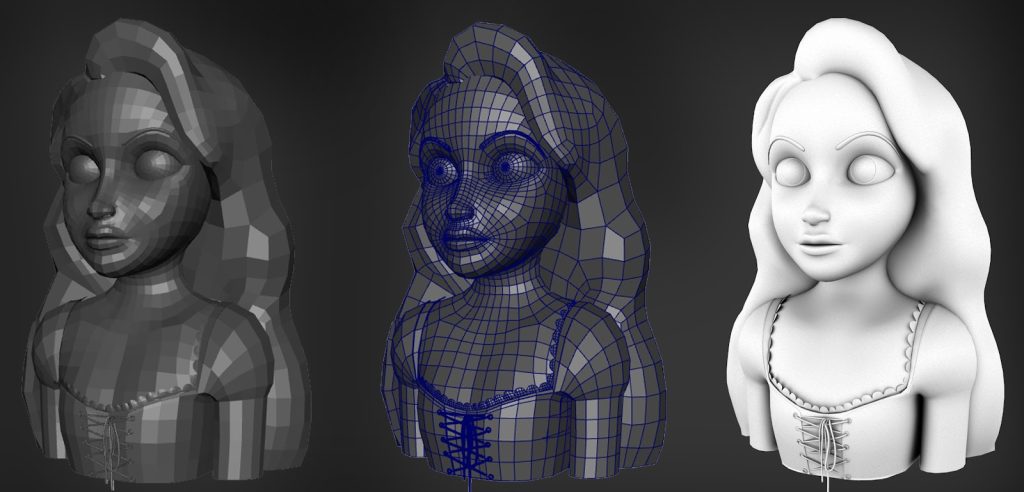

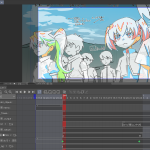

With the advent of digital technology in the 2000s, Asian animation entered a new era. Digital ink and paint systems replaced labor-intensive cel animation, while 3D modeling and computer-generated effects enhanced storytelling possibilities.

Japanese anime series such as Death Note (2006) and Attack on Titan (2013) utilized a combination of traditional 2D artistry and digital effects, resulting in visually striking and internationally acclaimed productions.

In China, digital platforms like Bilibili and Tencent Video facilitated the rise of donghua, with series such as The King’s Avatar and Fog Hill of the Five Elements gaining global attention. Similarly, South Korea’s manhwa adaptations and webtoon-based animations leveraged digital tools for streamlined production and widespread accessibility. Across the region, Asian animation embraced streaming platforms, social media, and global distribution, allowing audiences worldwide to experience culturally rich storytelling.

Key Characteristics of Asian Animation

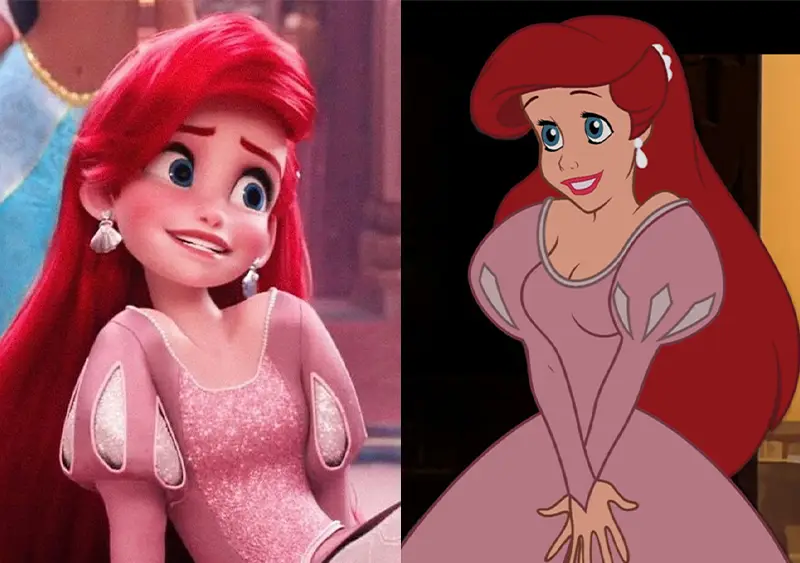

Asian animation is distinct for several defining characteristics. Stylistically, it often features exaggerated facial expressions, expressive eyes, and detailed backgrounds. Narrative depth is another hallmark, with storylines frequently exploring complex themes such as morality, identity, and human relationships.

Additionally, genre diversity, from mecha and fantasy to slice-of-life and horror, ensures that Asian animation appeals to a wide range of audiences, transcending age and cultural boundaries.

Cultural nuance plays a significant role as well. Japanese anime often incorporates elements of Shintoism, folklore, and societal commentary, while Chinese donghua may draw from classical literature, martial arts, or historical events. Korean animation integrates themes from webtoons, pop culture, and contemporary social issues.

This cultural specificity contributes to the global appeal of Asian animation, providing a window into the societies from which it originates.

The Global Impact of Asian Animation

Over the past few decades, Asian animation has grown from a regional phenomenon into a global powerhouse. Anime conventions, streaming services, and international film festivals have brought Japanese, Chinese, and Korean animations to audiences worldwide.

Series like Naruto, One Piece, and Demon Slayer have not only captured massive fan followings but also influenced Western animation styles and storytelling approaches.

Furthermore, Asian animation has inspired collaborations between Eastern and Western studios, blending aesthetic and narrative traditions. For instance, Netflix and Crunchyroll have invested heavily in producing and distributing original anime, making the genre more accessible than ever. This cross-cultural exchange demonstrates how Asian animation continues to innovate while maintaining its unique identity.

Technological Tools and Software in Asian Animation

Modern Asian animation relies heavily on both 2D and 3D digital tools. Software such as Toon Boom Harmony, Clip Studio Paint, and TVPaint facilitates traditional-style frame-by-frame animation, while Blender and Maya support 3D modeling, rigging, and rendering for hybrid projects. Studios often integrate multiple tools to achieve the desired aesthetic, combining hand-drawn artistry with digital efficiency.

This blending of traditional techniques and modern technology allows animators to maintain the expressive charm of hand-drawn animation while leveraging the speed, scalability, and visual enhancements of digital tools. For audiences, this results in richly detailed worlds, fluid character movements, and visually compelling narratives that resonate globally.

Contemporary Trends in Asian Animation

Today, Asian animation continues to evolve, reflecting changing audience preferences, technological advancements, and cross-media storytelling. Key trends include:

- Streaming-first content: Platforms like Netflix, Crunchyroll, and Bilibili prioritize accessibility, allowing series to reach global audiences instantly.

- Hybrid animation styles: Combining 2D and 3D techniques creates visually unique projects that stand out in a crowded market.

- Interactive and mobile-focused animation: Webtoons and app-based animations in South Korea and China are integrating gamified elements and interactive storytelling.

- Cultural exports: The global popularity of anime has influenced Western studios, encouraging collaborations and cross-cultural content creation.

These trends highlight the ongoing innovation and adaptability of Asian animation, ensuring it remains a vibrant and influential sector within the global entertainment industry.

Conclusion

The history and evolution of Asian animation demonstrates a remarkable journey from early hand-drawn experiments to globally recognized digital masterpieces.

Characterized by artistic innovation, cultural depth, and genre diversity, Asian animation continues to shape global storytelling. With advancements in technology, cross-cultural collaborations, and streaming accessibility, the influence of Asian animation is poised to grow even further, inspiring new generations of creators and audiences worldwide.

FAQ

Q1: What is Asian animation?

Asian animation refers to animated works originating in countries such as Japan, China, and South Korea, encompassing anime, donghua, and manhwa adaptations.

Q2: How is Asian animation different from Western animation?

Asian animation often emphasizes detailed character designs, complex narratives, emotional depth, and cultural themes, while Western animation may prioritize humor, simplicity, and broader appeal.

Q3: What software is used for Asian animation?

Popular tools include Toon Boom Harmony, Clip Studio Paint, TVPaint for 2D animation, and Blender or Maya for 3D projects or hybrid styles.

Q4: What are some famous examples of Asian animation?

Japanese anime like Naruto, Attack on Titan, and Spirited Away; Chinese donghua such as The King’s Avatar; and Korean webtoon adaptations are all widely recognized.

Q5: Why has Asian animation become globally popular?

Its unique artistic style, engaging storytelling, cultural depth, and accessibility through streaming platforms have attracted international audiences and influenced global media.